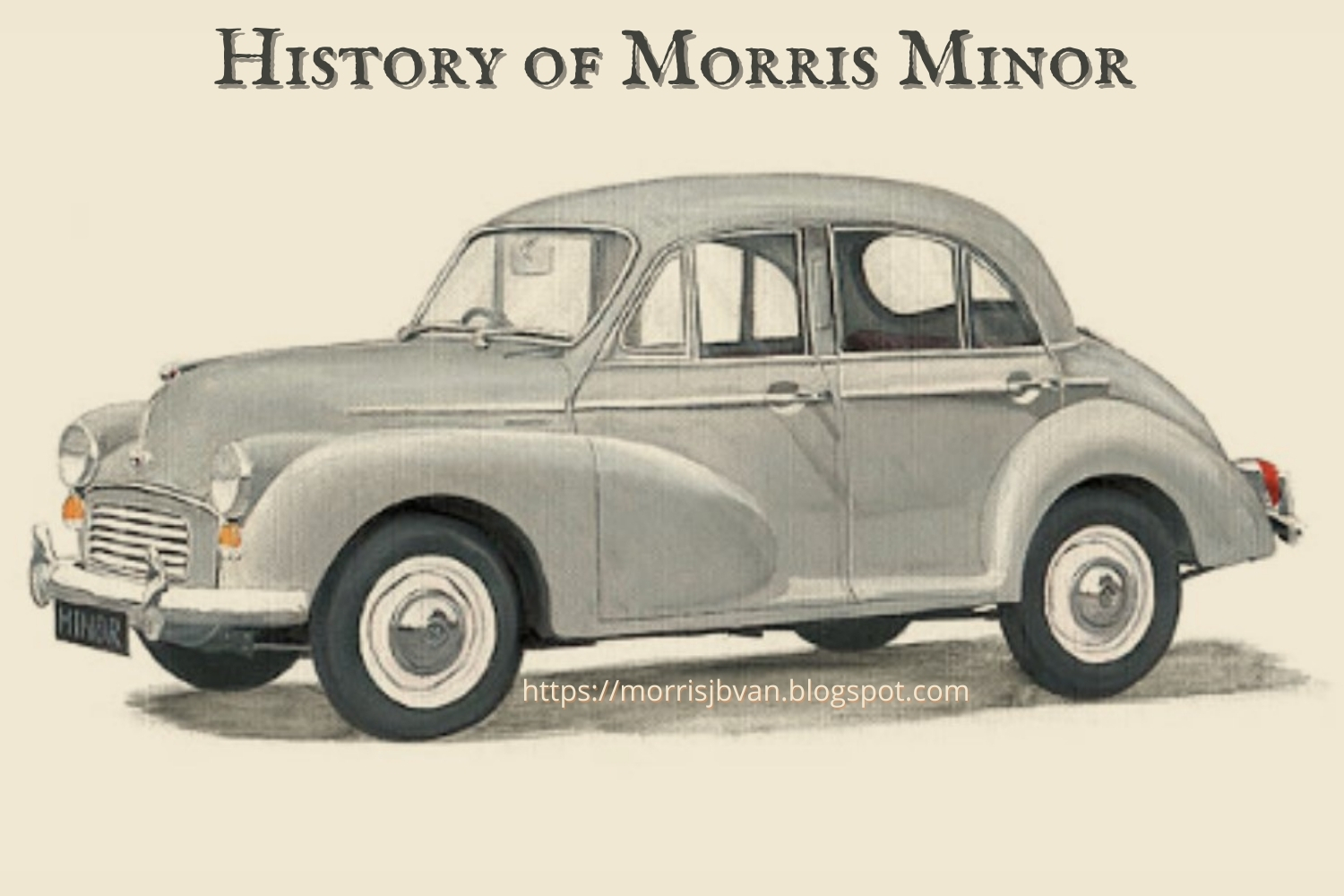

A Short History of Morris Minor

One of the best served old cars in Britain with hundreds being used as daily transport, the Morris Minor is perhaps the ultimate practical classic. With a dependable 1000cc engine returning 40 mpg, iconic styling, rugged and reliable running gear, and space for four adults and their luggage, it is a convincing and viable alternative to the Japanese superminis of the British high street.

The Minor story began in 1943 when Lord Nuffield, head of Morris Cars, instructed the gifted automotive designer Alec Issigonis to create a small, economical family car that could be built cheaply and sold in the thousands to get postwar Britain moving. At a time of austerity when the motorcar was still very much a preserve of the rich, and export to America offered the biggest profit margin, this was a progressive decision, probably influenced by the success of rival Austin's 'Seven', which had dominated cheap British motoring in the interwar years.

By the end of the War, Issigonis had brought together the basis of what would become the Minor, although the final recipe yet to be decided. Developed under the codename 'Mosquito', Issigonis intended to create a radical transverse engine layout which would power the front wheels of the car to increase passenger space in the cabin. Sadly, this design along with a number of other innovative ideas never made it off the page, but remained developing and maturing in his mind for a further 15 years until the launch of the mold-breaking Mini in 1959.

|

| Mosquito Prototype |

The Minor was launched at the London Motor Show in 1948. Although somewhat overshadowed by the sensational new Jaguar XK120, it was easily the most significant new British car of the year, if not the decade.

Construction was a significant step forwards in its class, being a form of semi-monocoque that gave the car remarkable rigidity and improved handling over the reheated prewar separate chassis designs that vied with it for sales. Styling was also considerably modern, completely doing away with the separate running boards that had characterized prewar design in favour of a fully integrated body, reflective of the postwar streamlining design movement. Headlamps set low into the grille preserved the clean lines of the shape, and with the option of 2-door saloon or 'Tourer' (convertible) bodies, the Minor represented a considerably attractive purchase in the otherwise dreary motoring landscape of postwar Britain.

However, the compromises made at the development stage over the car's power train tarnished its otherwise unblemished appeal. Having expended a considerable sum on the development of the body, simplicity and convention had been the order of the day for much of the running gear in order to ensure cheap manufacturing, running and servicing costs.

The radical transverse engine and front-wheel drive configuration had been dropped fairly early on in favour of a longitudinally mounted engine, transmitting drive through a 4-speed manual gearbox (without synchromesh on 1st and 2nd gears) to a live rear axle suspended by conventional leaf springs with lever arm dampers. The engine chosen by Issigonis for this configuration was a smooth, refined and reasonably powerful water-cooled aluminium 1483cc flat-four with overhead valve gear developed by Jowett in the early Thirties.

The distinctive broad and shallow engine bay of the early 'low-light' Minors bears testament to the intended application of this engine, but cost considerations and concerns not to become reliant on external suppliers prompted Morris to make the executive decision to reuse the flaccid and far heavier 918cc side-valve cast-iron 4-cylinder from the prewar Morris Eight, which gave mediocre performance at best.

Nevertheless, there were some more modern (if not wholly progressive) aspects to the running gear which made for a responsive and exciting drive by the standards of the day. The unitary construction of the Minor's body effectively did away with a conventional chassis (although there were welded-on chassis legs at the front and rear to support the engine and rear leaf springs), creating an enormously stiff shell with impressive torsional rigidity.

This approach also negated the need for a front engine and suspension sub-frame. As such, the front suspension was comprised of a primitive but very effective double-wishbone setup, using lever arm dampers as the top links and a pair of torsion bars as the springing medium, giving a fully independent system.

To control the steering, a very simple and efficient rack and pinion setup was adopted, offering extraordinary steering precision through a remarkably fast rack - just 2 and a half turns lock-to-lock! This coupled to the drastically unbalanced weight distribution (60/40 biased towards the front!), live rear axle and skinny tyres, gave a beautifully nimble car, which was responsive, direct and positive in the dry, and controllably tail-happy in the wet! The long gear lever and greater precision of the later gearboxes further added to the positive driving experience, which - for the stiffer saloon models at least - was virtually unrivalled in its class.

In 1952, Morris' parent company the Nuffield Group agreed to a merger with long-term rivals Austin to form the British Motor Corporation (BMC), the largest motor company in Britain and the fifth largest worldwide. This deal held a significant advantage to the Minor, allowing Morris to replace its outdated side-valve engine with the Austin 'A-Series' engine, which had been developed for the Minor's rival, the A30. This engine, which was of almost entirely new design, used a cylinder head with overhead valve gear, giving a useful improvement in power, economy and credibility - side valve engines had become obsolete at all levels of motoring in Britain by about 1950.

A new gearbox of light-weight cast aluminium alloy construction with synchromesh on 2nd, 3rd and 4th gears complemented the new engine, giving the Minor a new lease of life that helped to ensure its continued market presence into the Fifties. Launched in late 1952 as the Series II, the only other significant change was the moving of the headlights from the grille to the wings.

|

| 1953 Morris Minor Series II |

This was done to conform to American headlight regulations, but created entirely by accident the ubiquitous Minor 'face' beloved of so many. The model range was also expanded significantly to cater for a number of different market tastes and so increase salability. A 4-door version of the saloon had appeared in 1950, and was now joined by a closed van, pick-up truck and wooden-bodied estate, known as the 'Traveller'.

|

| Morris Minor 1000 Traveller |

The most significant change in the Minor's life occurred in 1956 when the 803cc A-series engine was increased in capacity to 948cc to create the Minor 1000, further benefitting performance and usability. Other refinements included replacing the split-windscreen with a single piece of curved glass and enlarging of the rear windscreen. Visually, a broader grille with horizontal slats was the most noticeable change externally, whilst inside the dashboard was completely remodelled following the moving of the single dial to the famous central position.

Deluxe versions of the Minor range became available in the mid-Fifties to maintain the cars' appeal in an increasingly diverse and competitive marketplace. For the modest sum of £30 or so, a cabin heater with demist facility, wing mirrors, bumper overriders, a passenger sun visor, heated rear windscreen element, and chrome-plated number plate lamp housing were available to the owner who required a little more refinement at the wheel.

In 1961, the Minor became the first British car to sell more than 1,000,000 units: a monumental achievement given that the Austin A30, its in-house competitor, had scarcely managed a third of that figure in the same time.

In 1962, the Minor received its final upgrades when a new 1098cc version of the A-series engine was transplanted in place of the 948cc unit across the entire Minor model range. However, beneficial as this change was to the Minor's appeal and usability, it exposed an internal conflict between two of the British Motor Corporations core products.

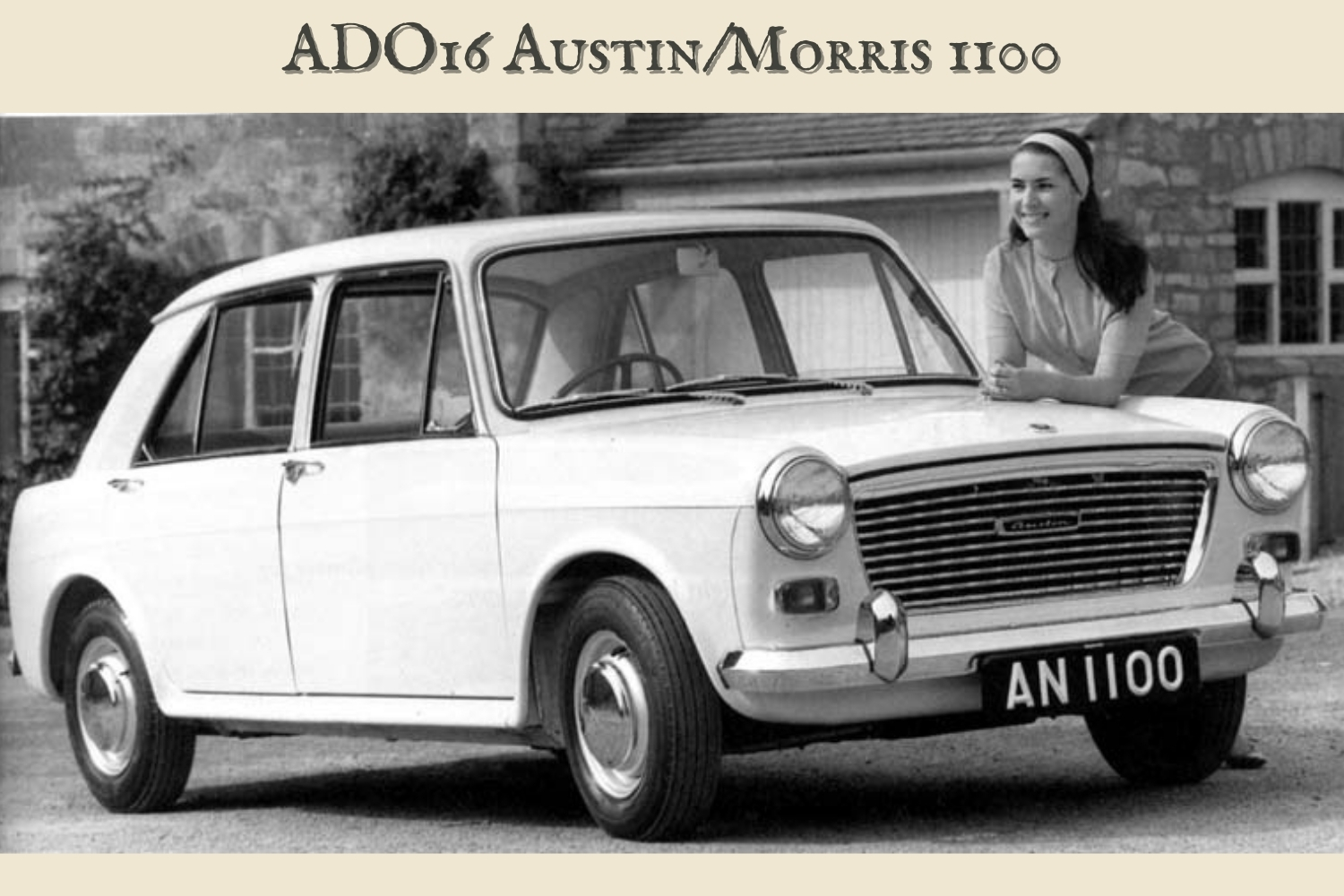

In the same year, BMC launched the all-new Issigonis-design ADO16 Austin/Morris 1100 range. Essentially a scaling-up of the Mini principle, the 1100 was to become Britain's best-selling and most advanced small family car, and in all respects - space, price, performance, specification - was designed to directly replace the Minor. However despite this, the Minor remained in continuous production, placing both the new and the old car in a very ill-defined portfolio.

|

| ADO16 Austin/Morris 1100 |

Development of ADO16 has been costly, but it was intended to sell in huge volumes and remain competitive into the early Seventies. For that reason, BMC consulted cylinder head specialist Harry Weslake (a pivotal member of the team behin Jaguar's exception twin-cam XK engine) to develop a more efficient and more powerful iteration of the ubiquitous A-series engine.

He opted for a long-stroke block with realigned and enlarged bore spacing giving a swept volume of 1098cc, onto which he grafted a new cylinder head with 'lean burn' semi-hemispherical combustion chambers. So strong and effective was this engine configuration that it went on to become the basis of the infamous 1275cc 'S' engines developed by John Cooper for the phenomenal Mini Cooper S of the mid 1960s.

The fitting of the 1100 engine, along with larger brakes, improved external lighting and a revised dashboard, was sufficient for the Minor upgrade to be issued its own in-house development code, ADO59, although the commercial name remained 'Minor 1000' so as not to generate confusion between it and the Morris 1100, the Morris-badged version of ADO16.

The impressive torque characteristics of the reworked engine made the Minor much more responsive in all driving conditions, and better suited to the long-distance motorway cruise that was becoming evermore popular in the early Sixties. All this pointed to the fact that BMC were not planning for the Minor's retirement, but were easing it into something of an Indian Summer.

At this stage in 1962, the Minor was in its fifteenth production year, but in terms of driving reward had just reached its zenith, with a torquey punch from its new engine. This had the unorthodox consequence of placing the Cowley factory where the Minor was built into direct competition with Longbridge, where Austin/Morris 1100 production had just begun: both were part of the same organization.

This bizarre system of internal competition between factories and models is reflective of the split personality of BMC in this era: on the one hand Issigonis and a team of skilled engineers were designing an entire range of thoroughly modern family cars fit for the 1960s and beyond, whilst on the other contractual obligations to the hundreds of factories and assembly plants throughout its vast empire prevented BMC from taking many of the aging postwar designs out of production without risking crippling labour disputes or mass redundancies.

It was a rock and a hard place, as profit margins collapsed under the financial constraint of building multiple completely separate cars for individual markets.

Component rationalization was about the only way to achieve anything approaching a streamlined business model, and it is probably for this reason rather than any earnest developmental strategy that the Minor received a new lease of life with the 1098cc engine. When all was said and done, a sale was a sale.

Sadly, this 'make-do and sell' attitude pervaded the whole of British Motor Corporation: every Mini was famously sold at a loss due to the cost of sustaining two identical production lines in different factories, and many of the other new Issigonis designs found themselves unprofitable after sales figures failed to meet expectations due in no small part to internal competition with other models!

BMC was ailing under its own weight, and grossly financially unstable. The dire situation eventually prompted a Government-backed merger with the hugely profitable Jaguar Cars in 1966, and a subsequent second merger with the financially prudent and commercially strong Leyland Motor Corporation, containing Standard-Triumph, the Leyland commercial vehicles, and latterly Rover/Alvis. All of these came together to form the British Leyland Motor Corporation (BLMC) in 1968.

The last Minor rolled off the production line in September 1971, 23 years and 1.6 million cars after production had begun. It is testament to the strength of the Minor's original design that, despite the unorthodox structure of BMC, it remained competitive in production for almost 10 years after the introduction of its successor. Just 2 years later, ADO16 was withdrawn in anticipation of the innovative yet under-developed Austin Allegro.

But the Minor's story did not end completely there. Its production lines in the Cowley factory were adapted soon after the end of production to accommodate production of the new Morris Marina, which was designed to compete with Ford's conservatively engineered Escort in low price, high volume fleet market.

To streamline development and minimize retooling costs, the Marina employed a floorpan and running gear deliberately similar to the Minor, and much of the floors, suspension and drivetrain is interchangeable. After a facelift and name-change to Morris Italy in 1980, the car soldiered on until its eventual withdrawal in 1984 ahead of the launch of the Maestro/Montego range. Over 40 years had passed since the Minor had been developed and the production lines built. It had been the unchanging constant during the most progressive and radical years of the British Motor Industry's story.

Once a common sight on UK roads, the Minor has become more elusive over recent years. That said, along with Minis and MGBs, it remains one of the most popular classics to own in Britain, with its appeal seeming to transcend all barriers of age and gender. It is surely the quintessential classic.

Morris Minor Buying Guide

For those looking for a route into classic ownership, the Morris Minor is hard to beat as a first car. Parts availability is second to none, with virtually every part available off-the-shelf. And with a plethora of web-based mail-order suppliers competing for your custom, prices remain absurdly low. The simplicity of the Minor's running gear make them very easy to work on, and there are very few jobs an enthusiast cannot accomplish with just a set of ring-spanners and a few sockets.

As with all classics of this period, rust is the biggest killers. Avoid taking on a car with major rot in either of the front chassis rails, central crossmember, rear suspension mountings or A-pillars, as these areas are prohibitively costly to repair. Vans and Pick-ups are the only Minors with a separate chassis, and should be inspected thoroughly.

Convertible Tourer models are likely to have rotten floors and bulkheads if water has been allowed to ingress. 4-door saloon models may also have suffered if the door seals have not been maintained. The condition of a Traveller's wooden frame is also crucial to the car's structural integrity, and rotten or inadequately repaired examples should be avoided. The 2-door saloon is by far the most common body style on the roads today, and offers the stiffest shell with fewest areas for water to creep in.

Of the engine choices, the 918cc side valve unit is confined almost exclusively to the early 'low-light' models unless a previous owner has departed from originality to retro-fitted a later engine. The 803cc A-series in post-1952 models are still underpowered, but can be swapped for most versions of the A-series relatively straightforwardly. The 948cc A-series from the post-1956 Minor 1000 models is the sweetest engine, being smooth and well balanced, whereas the 1098cc engine from the post-1962 cars offers impressive torque for punchy and responsive acceleration in favour of refinement.

Modifications are surprisingly easy to achieve, with many conversion kits available off-the-shelf. Disc brakes, servo-assist, telescopic shock absorbers, and larger 1275cc engine swaps seem to be the most popular and effective modifications for modern urban traffic use, most of which is easily transplanted from the Marina. Originality is only really prized on the early 'low-light' models, so don't be put off by 5-speed gearbox conversions or alternative engines. As with all classics, buy the best you can afford and prioritise your budget sensibly - £400 is much better spent on a brakes upgrade than a respray.

Morris Minor Prices

With over 1.6 million built, Morris Minors are still in plentiful supply. That said, depending on age, condition and model, Minors can change hands for tidy sums of money. The later 1098cc Minor 1000s are the most practical for use in modern traffic, although the earlier 'low light' Series MM cars command a small premium for collectors.

Expect to pay £6000 for a Condition 1 saloon, £6500 for the equivalent Tourer and upwards of £7000 for a Traveller, Van or Pick-up. Usable cars are in ready supply from £1500, whilst a project can still be picked up for a few hundred pounds. Priced alongside the equivalent Japanese supermini, a Minor can seem like a sound investment. It is highly unlikely to depreciate, easy to maintain, and if serviced properly can cover impressive mileage without major issue.